The fascinating story of why the ‘first’ Ryder Cup was scrubbed from the record books

Last updated:

Among our sport’s glorious history lies a murky tale of the very first Ryder Cup that ended up being expunged. This is the story of the 1926 match that – officially, at least – never happened…

The Ryder Cup we know today could just as easily been known as the Ross Cup, the James Harnett Cup, or, wait for it, the Sylvanus P Jermain Cup. The idea to stage an international challenge match between teams of professional golfers from Britain and the United States was not a new one.

While details are sketchy, the man credited with the original concept was Ohio businessman SP Jermain. Instrumental in inviting English professionals Harry Vardon and Edward Ray to compete in the 1920 US Open at his home club of Inverness, he believed that an international match between these two great golfing nations should be encouraged. Aware of this, Walter Ross, President of the Nickel Plate Railroad Company in Cleveland, even offered to pay for a trophy.

That same year of 1920 also saw American golf star Walter Hagen put his considerable weight behind the idea, and he was enthusiastically backed by James Harnett, circulation manager of Golf Illustrated in New York. Looking to increase readership figures, Harnett began raising the necessary funds to send an American team to Britain, but came up short of his target.

A meeting was hastily convened with the United States Professional Golfers’ Association on December 15th, which found the money he needed for the match. With each player offered $1,000 to cover their expenses, the match was given the green light, and while the Ryder Cup itself was still seven years’ distant, the idea behind what has become the most eagerly contested team event in world golf had effectively been born.

Scheduled for June 6, 1921, the match was to be played at Gleneagles in Perthshire. Having arrived in Southampton, the American team made their way to Glasgow by sleeper train. The match was run in conjunction with the Glasgow Herald 1000 Guinea Tournament, a grand affair with a huge prize fund which attracted the top names in British golf, including six-time Open champion Harry Vardon.

With the famous hotel still under construction, accommodation consisted of five railway carriages moved into the sidings at the railway station near Auchtermuchty, and the teams were forced to fetch and carry their own water for much of the week.

Huge crowds came to see George Duncan pick up the first prize of £160 in the Glasgow Herald Tournament, but then disappeared when the international challenge got underway. Press and public alike considered it little more than an elaborate exhibition.

Apart from two-time US Open winner Walter Hagen, the American team hardly sparkled with talent. Therefore, it came as no surprise when the outspoken professional Andrew Kirkaldy predicted a complete whitewash. “It will be too one-sided,” he said. “The Americans haven’t a chance.” The sage of St Andrews was proved right. Great Britain trounced their visitors 9-3, with three matches halved.

Despite the carping criticism the contest attracted from the press, Hagen never quite gave up on the idea, and when the opportunity arose again to play in another Britain versus America match, six years later, he gladly accepted. This was also the first time that Hagen encountered a seed merchant from St Albans called Samuel Ryder, a successful businessman who made his fortune selling packets of seeds through the post for a penny.

Sowing the Seed

Born in March 1858, Ryder, the son of a Manchester corn merchant, left the family firm at a young age and moved south to St Albans. Along with his younger brother James, he formed the Heath & Heather Seed Company in 1898, before establishing Ryder and Son.

A tall, slender man who hid a mischievous smile beneath a bushy moustache, Ryder was a tireless worker. A pillar of the local community in later life, he not only maintained close ties with his own business but also served as town mayor, justice of the peace, and church deacon. Indeed, it was following advice from his church minister, the Reverend Francis Wheeler, that he reluctantly took up golf at the relatively advanced age of 50.

Suffering from ill health, Ryder was forced to give up his first love of cricket and decided to play golf in preference to bowls. In the spring of 1909, he hired local club pro John Hill to come to his mansion six days a week to give him lessons. (A deeply religious man, Ryder never played golf on the Sabbath.) Playing off an unofficial handicap of six, he felt sufficiently confident to join nearby Verulam a year later and was soon elected Club Captain.

In 1923, Ryder took his interest in golf one stage further when his Heath & Heather company sponsored a tournament, the first of seven events he and James would support between 1923 and 1925.

Also held at Verulam, he stunned everyone by paying all competitors an appearance fee of £5, with £50 going to the winner.

Attracting star names such as Duncan, Harry Vardon, James Braid, and Sandy Herd, it was eventually won by Arthur Havers, who had just won The Open at Troon. Havers’s prize was just £25 less than he got for winning the most famous title in golf!

One of the professionals competing in the event was Englishman Abe Mitchell. A shy, courteous man, Mitchell was arguably the best player never to have won The Open, and he supplemented his relatively meagre existence as club pro at North Foreland Golf Club by playing in exhibition matches.

Ryder and Mitchell became good friends, and in December 1925, Ryder offered Mitchell a three-year contract, at the princely sum of £500 per year, to become his personal tutor. Adding £250 to cover his tournament expenses, it was hoped that by freeing him from club responsibilities, he could focus on winning The Open. Sadly, he was never to realise that dream.

Mitchell was also instrumental in sparking Ryder’s interest in the professional game over the coming years. By the mid-1920s, the golden era of Vardon, Braid, and Taylor was over, but dashing young professionals like Duncan had emerged, and British golf was increasingly buoyant in the face of strong American opposition. As such, the Open Championship had proved an intriguing battleground. Not surprisingly, clubhouse talk often revolved around which was the stronger golfing nation.

The first opportunity to find the answer came at Wentworth in 1926. The history books show that the first Ryder Cup took place in 1927 in Worcester, Massachusetts. Some say it began one year earlier at Wentworth. So what is the truth?

Most people believe that an informal match was played between British and American professionals in June 1926. A fairly relaxed affair, the home team dusted off their opponents in a very one-sided encounter by 13½ points to 1½. After the match, both teams retired to the clubhouse (opened in 1924), for champagne and chicken sandwiches.

Little more than an interested spectator, Samuel Ryder was said to have marvelled at the camaraderie shown by both teams before announcing, “We must do this, Ernest Whitcombe, Herbert Jolly, Aubrey again!”

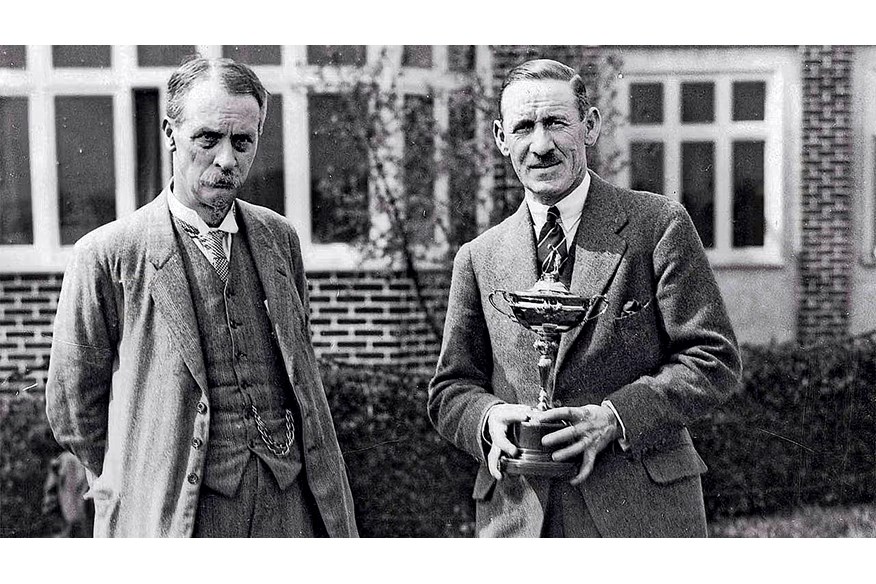

Agreeing to provide a trophy, he commissioned London silversmiths Mappin and Webb to make a golden chalice adorned with the figure of his coach and friend Mitchell. A year later the two teams met again in Worcester, Massachusetts, to play for old Sam’s Cup – and the biennial match was born. The truth, however, is a little different.

An Eclectic Ensemble

With entries to the 1926 Open at Royal Lytham & St Annes oversubscribed, the Royal & Ancient decided to hold three regional pre-qualifying events at Sunningdale in Surrey, St Annes Old in Lancashire, and Western Gailes in Ayrshire.

This decision was announced at the end of 1925, and it meant Sunningdale was chosen to host the dozen or so American players – including the great Bobby Jones – who were expected to arrive in Southampton a week earlier. Ultimately, it was this decision that would prove the trigger for the first Ryder Cup.

Early in 1926, an invitation had gone out asking if a representative team of American professionals wanted to take part in an international match against their British counterparts at nearby Wentworth. Never one to turn down an invitation, Hagen had accepted on behalf of his countrymen, and the match was set for June 4-5. No doubt seen as a gentle warm-up to the serious business of Open qualification, the British PGA probably didn’t officially endorse the invitation. It is much more likely that Samuel Ryder saw it as a useful marketing exercise for his company.

Writing in the Daily Telegraph in 1925, George Greenwood noted that the Ryder brothers were “two keen golfers and enthusiastic sportsmen who originated the idea of an annual match between American and British golfers of front rank.”

Then, on April 26, 1926, it was announced in the press that “Mr S Ryder, of St Albans, has presented a trophy for annual competition between teams of British and American professionals. The first match for the trophy is to take place at Wentworth on June 4th and 5th.”

From this, we can conclude that Sam and James Ryder had already seen the possibility of a Britain versus the United States match every year. And it made sense to hold this before The Open Championship. Described in May 1926 as a “Walker Cup for professionals”, Wentworth was chosen partly because of the quality of the course, and also because of its close proximity to the Open qualifying tournament at Sunningdale.

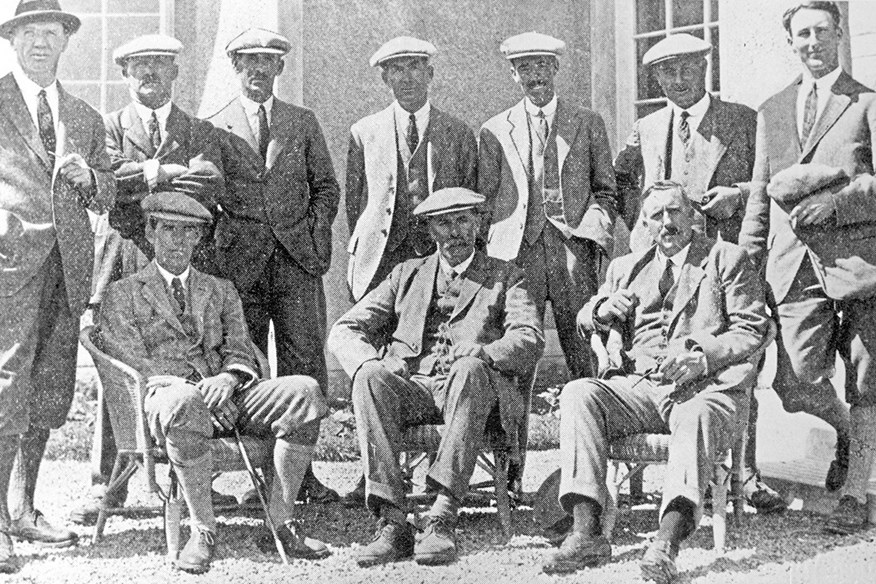

Played over the fledgling West Course match, the British team boasted former Open Champions in Ray (1912), Duncan (1920), and Havers (1923). Alongside them were experienced campaigners Mitchell, Archie Compston, Fred Robson, Ernest Whitcombe, Herbert Jolly, Aubrey Boomer, and George Gadd.

It came as little surprise when the home team made the perfect start by winning all five foursomes. Then, in one of the nine singles scheduled for the following day, Duncan destroyed the great Hagen by 6&5. In another, Mitchell thrashed Jim Barnes 8&7. It was no surprise that the match ended in a very comfortable victory for the home team.

So why has this match been struck from the records? The reason is simple, as a report from Golf Illustrated, dated June 11, 1926, clearly shows.

Under the headline, ‘The Ryder Cup’, it explains that: “Owing to the uncertainty of the situation following the [General] Strike in which it was not known until a few days ago how many American professionals would be visiting Great Britain, Mr J Ryder decided to withhold the Cup, which he has offered for annual competition between the professionals of Great Britain and America.

“Under these circumstances, the Wentworth Club provided the British players with gold medals to mark the inauguration of this great international match.”

So there we have it. The General Strike, which lasted from May 3 to 12, had ruined the travel plans of the American team, forcing Sam Ryder to come up with an alternative solution.

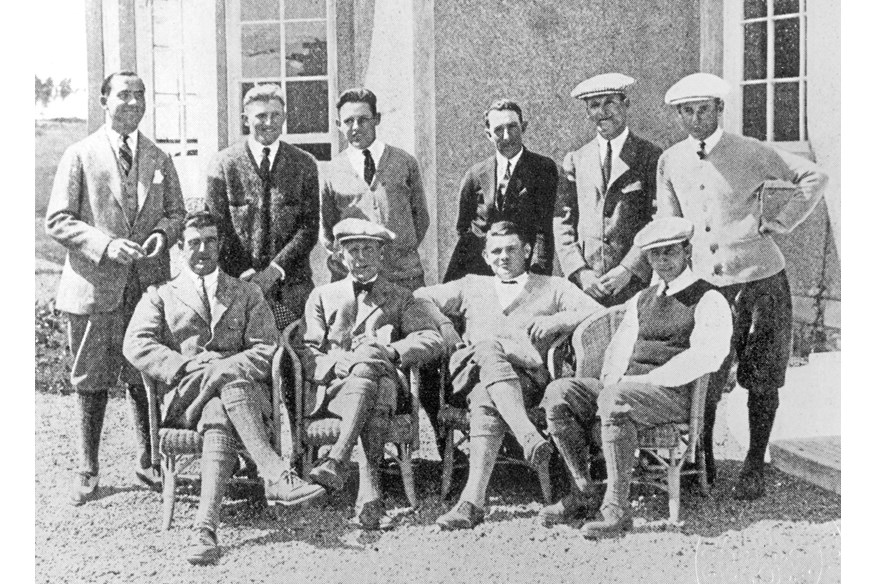

Rather than cancel the inaugural match, the United States team ‘invited’ a number of non-Americans to make up the numbers. So, along with Walter Hagen, Bill Mehlhorn, Al Watrous, Cyril Walker, and Emmett French, two Scots in Fred McLeod and Tommy Armour, two Englishmen in Jim Barnes and Joe Stain, and an Australian trick-shot artist by the name of Joe Kirkwood were recruited to make up the numbers!

With that type of eclectic international line-up, there was never any chance that the United States PGA would sanction the result when it was approached a short time later about making the Ryder Cup an official event.

Expunged from the record books forever, the tale about Duncan casually suggesting to Ryder afterwards that a trophy might be donated is quite simply untrue. However, if it did happen that way, as Ryder’s daughter Joan Ryder-Scarfe said it did, then perhaps Duncan was simply unaware that Ryder had a trophy ready for the next match.

As The Times reported on Wednesday, June 2, 1926, “The first important match in which the American professionals will take on a team of British professionals for the Ryder Cup will be at Wentworth next Friday and Saturday.”

Proof, if proof were needed, that the Ryder Cup trophy had been put up as a prize by the time the first shot was struck at Wentworth in June 1926. The fact that it wasn’t actually presented was due to the non-American nature of the American team. Bearing a ‘1927’ hallmark, it is unlikely that old Sam had it ready in time, despite all the pre-match publicity.

Splitting the cost between Ryder (£100), Golf Illustrated (£100), and the Royal & Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews (£50), the history books show that the first time it was actually seen in public was when Great Britain took on the United States 12 months later in Worcester, Massachusetts.

- NOW READ: A brief history of the Ryder Cup trophy